Introduction

This is the Redox OS book, which will go through (almost) everything about Redox: design, philosophy, how it works, how you can contribute, how to deploy Redox, and much more.

Please keep in mind that this book is work-in-progress and sometimes can be outdated, any help to improve it is important.

If you want to skip straight to trying out Redox, see the Getting started page.

If you want to contribute to Redox, read the following guides: CONTRIBUTING and Developing for Redox.

Conventions

Notices

The following notices are commonly used throughout the book to convey noteworthy information:

| Notice | Meaning |

|---|---|

| 🛈 Info | Provides neutral information to deliver key facts. |

| 📝 Note | Provides information to enhance understanding. |

| 💡 Tip | Offers suggestions to optimize an experience. |

| ⚠️ Warning | Highlights potential risks or mistakes. |

What is Redox?

Redox OS is a general-purpose operating system written in Rust. Our aim is to provide a fully functioning Unix-like microkernel-based operating system, that is secure, reliable and free.

We have modest compatibility with POSIX, allowing Redox to run many programs without porting.

We take inspiration from Plan 9, Minix, seL4, Linux, OpenBSD and FreeBSD. Redox aims to synthesize years of research and hard won experience into a system that feels modern and familiar.

This book is written in a way that you doesn't require any prior knowledge of Rust or OS development.

Origin Story

Redox OS was created in 2015 before the first stable version (1.0) of the Rust compiler and was one of the first operating systems written in Rust. It started as an unikernel (without a hypervisor) and gathered the contributions of many Rust developers.

As the project progressed, Jeremy Soller decided that the OS should be focused on stability and security. To achieve that, Redox was redesigned to adopt a microkernel architecture and a unified system API for resources.

Minix and Plan 9 were the main inspirations for the system design in the beginning.

Introducing Redox OS

Redox OS is microkernel-based operating system, with a large number of supported programs and components, to create a full-featured user and application environment. In this chapter, we will discuss the goals, philosophy and scope of Redox.

Our Goals

Redox is an attempt to make a complete, fully-functioning, general-purpose operating system with a focus on safety, freedom, stabillity, correctness, and pragmatism.

We want to be able to use it, without obstructions, as a complete alternative to Linux/BSD in our computers. It should be able to run most Linux/BSD programs with minimal modifications.

We're aiming towards a complete, stable, and safe Rust ecosystem. This is a design choice, which hopefully improves correctness and security (see the Why Rust page).

We want to improve the security design when compared to other Unix-like operating systems by using safe defaults and limiting insecure configurations where possible.

The non-goals of Redox

We are not a Linux/BSD clone, or POSIX-compliant, nor crazy scientists, who wish to redesign everything. Generally, we stick to well-tested and proven correct designs. If it ain't broken don't fix it.

This means that a large number of programs and libraries will be compatible with Redox. Some things that do not align with our design decisions will have to be ported.

The key here is the trade off between correctness and compatibility. Ideally, you should be able to achieve both, but unfortunately, you can't always do so.

Our Philosophy

Redox OS is predominately MIT X11-style licensed, including all software, documentation, and fonts. There are only a few exceptions to this, which are all licensed under other compatible open-source licenses.

The MIT X11-style license has the following properties:

- It gives you, the user of the software, complete and unrestrained access to the software, such that you may inspect, modify, and redistribute your changes

- Inspection Anyone may inspect the software for security vulnerabilities

- Modification Anyone may modify the software to fix security vulnerabilities

- Redistribution Anyone may redistribute the software to patch the security vulnerabilities

- It is compatible with GPL licenses - Projects licensed as GPL can be distributed with Redox OS

- It allows for the incorporation of GPL-incompatible free software, such as OpenZFS, which is CDDL licensed

The license does not restrict the software that may run on Redox, however -- and thanks to the microkernel architecture, even traditionally tightly-coupled components such as drivers can be distributed separately, so maintainers are free to choose whatever license they like for their projects.

This license was chosen to allow Redox to be used everywhere with minimum restrictions.

Redox intends to be free forever, because we aim to be a foundational piece in creating secure and resilient systems.

Why a New OS?

The essential goal of the Redox project is to build a robust, reliable and safe general-purpose operating system. To that end, the following key design choices have been made.

Written in Rust

Wherever possible, Redox code is written in Rust. Rust enforces a set of rules and checks on the use, sharing and deallocation of memory references. This almost entirely eliminates the potential for memory leaks, buffer overruns, use after free, and other memory errors that arise during development. The vast majority of security vulnerabilities in operating systems originate from memory errors. The Rust compiler prevents this type of error before the developer attempts to add it to the code base.

It allows us to unlock the full Rust potential by dropping legacy C and C++ code.

Benefits

The following items summarize the Rust benefits:

-

Memory-Safety

All memory allocations are verified by the compiler to prevent bugs.

-

Thread-Safety

Concurrent code in programs is immune to data races.

-

NULL-Safety

NULLs can't cause undefined behavior.

Microkernel Architecture

The Microkernel Architecture moves as much components as possible out of the operating system kernel. Drivers, subsystems and other operating system functionality run as independent processes on user-space (daemons). The kernel's main responsibility is the coordination of these processes, and the management of system resources to the processes.

Most kernels, other than some real-time operating systems, use an event-handler design. Hardware interrupts and application system calls, each one trigger an event invoking the appropriate handler. The kernel runs in supervisor-mode, with access to all the system's resources. In Monolithic Kernels, the operating system's entire response to an event must be completed in supervisor mode. An error in the kernel, or even a misbehaving piece of hardware, can cause the system to enter a state where it is unable to respond to any event. And because of the large amount of code in the kernel, the potential for vulnerabilities while in supervisor mode is vastly greater than for a microkernel design.

In Redox, drivers and many system services can run in user-mode, similar to user programs, and the system can restrict them so they can only access the resources that they require for their designated purpose. If a driver fails or panics, it can be ignored or restarted with no impact on the rest of the system. A misbehaving piece of hardware might impact system performance or cause the loss of a service, but the kernel will continue to function and to provide whatever services remain available.

Thus Redox is an unique opportunity to show the microkernel potential for the mainstream operating systems universe.

Benefits

The following items summarize the microkernel benefits:

-

More stable and secure

The very small size of the kernel allow the system to be more stable and secure because most system components are isolated in user-space, reducing the chance of a kernel panic and the severity of security bugs.

-

Bug isolation

Most system components run in user-space on a microkernel system. Because of this some types of bugs in most system components and drivers can't spread to other system components or drivers.

-

More stable long execution

When an operating system is left running for a long time (days, months or even years) it will activate many bugs and it's hard to know when they were activated, at some point these bugs can cause security issues, data corruption or crash the system.

In a microkernel most system components are isolated and some bug types can't spread to other system components, thus the long execution tend to enable less bugs reducing the security issues, data corruption and downtime on servers.

Also some system components can be restarted on-the-fly (without a full system restart) to disable the bugs of a long execution.

-

Restartless design

A mature microkernel changes very little (except for bug fixes), so you won't need to restart your system very often to update it.

Since most system components are in userspace they can be restarted/updated on-the-fly, reducing the downtime of servers a lot.

-

Easy to develop and debug

Most system components run in userspace, simplifying the testing and debugging.

-

Easy and quick to expand

New system components and drivers are easily and quickly added as userspace daemons.

-

True modularity

You can enable/disable/update most system components without a system restart, similar to but safer than some modules on monolithic kernels and livepatching.

You can read more about the above benefits on the Microkernels page.

Advanced Filesystem

Redox provides an advanced filesystem, RedoxFS. It includes many of the features in ZFS, but in a more modular design.

More details on RedoxFS can be found on the RedoxFS page.

Unix-like Tools and API

Redox provides a Unix-like command interface, with many everyday tools written in Rust but with familiar names and options. As well, Redox system services include a programming interface that is a subset of the POSIX API, via relibc. This means that many Linux/POSIX programs can run on Redox with only recompilation. While the Redox team has a strong preference for having essential programs written in Rust, we are agnostic about the programming language for programs of the user's choice. This means an easy migration path for systems and programs previously developed for a Unix-like platform.

Redox Use Cases

Redox is a general-purpose operating system that can be used in many situations. Some of the key use cases for Redox are as follows.

Server

Redox has the potential to be a secure server platform for cloud services and web hosting. The improved safety and reliability that Redox can provide, as it matures, makes it an excellent fit for the server world. Work remains to be done on support for important server technologies such as databases and web servers, as well as compatibility with high-end server hardware.

Redox has plans underway for virtualization support. Although running an instance of Linux in a container on Redox will lose some of the benefits of Redox, it can limit the scope of vulnerabilities. Redox-on-Redox and Linux-on-Redox virtualization have the potential to be much more secure than Linux-on-Linux. These capabilities are still a ways off, but are among the goals of the Redox team.

Desktop

The development of Redox for the desktop is well underway. Although support for accelerated graphics is limited at this time, Redox does include a graphical user interface, and support on Rust-written GUI libraries like winit, Iced and Slint.

A demo version of Redox is available with several games and programs to try. However, the most important objective for desktop is to host the development of Redox. We are working through issues with some of our build tools, and other developer tools such as editors have not been tested under daily use, but we continue to make this a priority.

Due to a fairly limited list of currently supported hardware, once self-hosted development is available the development can be done inside of Redox with more quick testing. We are adding more hardware compatibility as quickly as we can, and we hope to be able to support the development on a wide array of desktops and notebooks in the near future.

Infrastructure

Redox's modular architecture make it ideal for many telecom infrastructure applications, such as routers, telecom components, edge servers, etc., especially as more functionality is added to these devices. There are no specific plans for remote management yet, but Redox's potential for security and reliability make it ideal for this type of application.

Embedded and IoT

For embedded systems with complex user interfaces and broad feature sets, Redox has the potential to be an ideal fit. As everyday appliances become Internet-connected devices with sensors, microphones and cameras, they have the potential for attacks that violate the privacy of consumers in the sanctity of their homes. Redox can provide a full-featured, reliable operating system while limiting the likelihood of attacks. At this time, Redox does not yet have touchscreen support, video capture, or support for sensors and buttons, but these are well-understood technologies and can be added as it becomes a priority.

Mission-Critical Applications

Although there are no current plans to create a version of Redox for mission-critical applications such as satellites or air safety systems, it's not beyond the realm of possibility. As tools for correctness proofs of Rust software improve, it may be possible to create a version of Redox that is proven correct, within some practical limits.

How Redox Compares to Other Operating Systems

We share quite a lot with other operating systems.

System Calls

The Redox userspace API is Unix-like. For example, we have the open, pipe, pipe2, lseek, read, write, brk, execv POSIX functions, and so on. Currently, we implement userspace analogues of most Unix-like system calls (on monolithic kernels). The kernel syscall interface itself is unstable and may not be similar at all, but is closely related to the higher-level POSIX APIs built on top of them, at the moment.

However, Redox does not necessarily implement them as system calls directly. Much of the machinery for these functions (typically the man(2) functions) is provided in userspace through an interface library, relibc.

For example, the open POSIX function is called SYS_OPEN on relibc.

"Everything is a File"

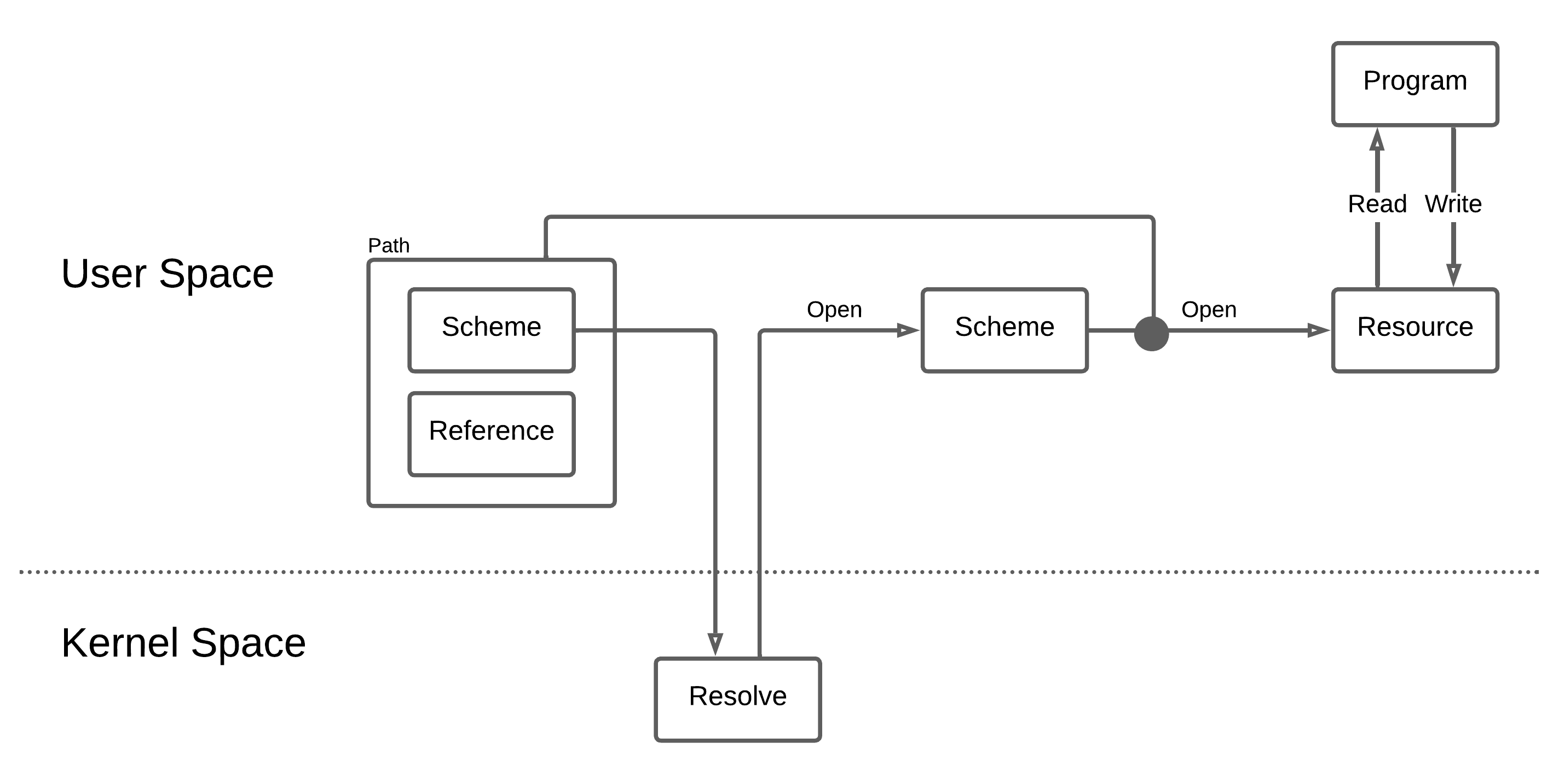

In a model largely inspired by Plan 9, in Redox, resources can be socket-like or file-like, providing a more unified system API. Resources are named using paths, similar to what you would find in Linux or another Unix system. But when referring to a resource that is being managed by a particular resource manager, you can address it using a scheme-rooted path. We will explain this later, in the Schemes and Resources page.

The kernel

Redox's kernel is a microkernel. The architecture is largely inspired by MINIX and seL4.

In contrast to Linux or BSD, Redox has around 50,000 lines of kernel code, a number that is often decreasing. Most system services are provided in userspace, either in an interface library, or as daemons.

Having vastly smaller amount of code in the kernel makes it easier to find and fix bugs/security issues in an efficient way. Andrew Tanenbaum (author of MINIX) stated that for every 1,000 lines of properly written C code, there is a bug. This means that for a monolithic kernel with nearly 25,000,000 lines of C code, there could be nearly 25,000 bugs. A microkernel with only 50,000 lines of C code would mean that around 50 bugs exist (Tanenbaum Law).

It should be noted that in a microkernel the high amount of code (present in a monolithic kernel) is not removed, it's just moved to user-space daemons to make it less dangerous.

The main idea is to have system components and drivers that would be inside a monolithic kernel exist in user-space and follow the Principle of Least Authority (POLA). This is where every individual component is:

- Completely isolated in memory as separated user processes (daemons)

- The failure of one component does not crash other components

- Foreign and untrusted code does not expose the entire system

- Bugs and malware cannot spread to other components

- Has restricted communication with other components

- Doesn't have Admin/Super-User privileges

- Bugs are moved to user-space which reduces their power

All of this increases the reliability of the system significantly. This is important for users that want minimal issues with their computers or mission-critical applications.

Why Rust?

Why we wrote an operating system in Rust? Why even write in Rust?

Rust has enormous advantages, because for operating systems, security and stability matters a lot.

Since operating systems are such an integrated part of computing, they are the most important piece of software.

There have been numerous bugs and vulnerabilities in Linux, BSD, glibc, Bash, X11, etc. throughout time, simply due to the lack of memory allocation and type safety. Rust does this right, by enforcing memory safety statically.

Design does matter, but so does implementation. Rust attempts to avoid these unexpected memory unsafe conditions (which are a major source of security critical bugs). Design is a very transparent source of issues. You know what is going on, you know what was intended and what was not.

The basic design of the kernel/user-space separation is fairly similar to Unix-like systems, at this point. The idea is roughly the same: you separate kernel and user-space, through strict enforcement by the kernel, which manages system resources.

However, we have an advantage: enforced memory and type safety. This is Rust's strong side, a large number of "unexpected bugs" (for example, undefined behavior) are eliminated at compile-time.

The design of Linux and BSD is secure. The implementation is not. Many bugs in Linux originate in unsafe conditions (which Rust effectively eliminates) like buffer overflows, not the overall design.

We hope that using Rust we will produce a more secure and stable operating system in the end.

Unsafes

unsafe is a way to tell Rust that "I know what I'm doing!", which is often necessary when writing low-level code, providing safe abstractions. You cannot write a kernel without unsafe.

In that light, a kernel cannot be 100% verified by the Rust compiler, however the unsafe parts have to be marked with an unsafe, which keeps the unsafe parts segregated from the safe code. We seek to eliminate the unsafes where we can, and when we use unsafes, we are extremely careful.

This contrasts with kernels written in C, which cannot make guarantees about security without costly formal analysis.

You can find out more about how unsafe works in the relevant section of the Rust book.

Benefits

The following sections explain the Rust benefits.

Less likely to have bugs

The restrictive syntax and compiler requirements to build the code reduce the probability of bugs a lot.

Less vulnerable to data corruption

The Rust compiler helps the programmer to avoid memory errors and race conditions, which reduces the probability of data corruption bugs.

No need for C/C++ exploit mitigations

The microkernel design written in Rust protects against memory defects that one might see in software written in C/C++.

By isolating the system components from the kernel, the attack surface is very limited.

Improved security and reliability without significant performance impact

As the kernel is small, it uses less memory to do its work. The limited kernel code size helps us work towards a bug-free status (KISS).

Rust's safe and fast language design, combined with the small kernel code size, helps ensure a reliable, performant and easy to maintain core.

Thread-safety

The C/C++ support for thread-safety is quite fragile. As such, it is very easy to write a program that looks safe to run across multiple threads, but which introduces subtle bugs or security holes. If one thread accesses a piece of state at the same time that another thread is changing it, the whole program can exhibit some truly confusing and bizarre bugs.

You can see this example of a serious class of security bugs that thread-safety fixes.

In Rust, this kind of bug is easy to avoid: the same type system that keeps us from writing memory unsafety prevents us from writing dangerous concurrent access patterns

Rust-written Drivers

Drivers written in Rust are likely to have fewer bugs and are therefore more stable and secure.

Side Projects

Redox is a complete Rust operating system. In addition to the Redox kernel, our team is developing several side projects, including:

- RedoxFS - Redox file system inspired by ZFS.

- Ion - The Redox shell.

- Orbital - The desktop environment/display server of Redox.

- pkgutils - Redox package manager, with a command-line frontend and library.

- relibc - Redox C library.

- audiod - Redox audio server.

- bootloader - Redox boot loader.

- init - Redox init system.

- installer - Redox buildsystem builder.

- netstack - Redox network stack.

- redoxer - A tool to run/test Rust programs inside of a Redox VM.

- sodium - A Vi-like editor.

- games - A collection of mini-games for Redox (alike BSD-games).

- OrbTK - Cross-platform Rust-written GUI toolkit (in maintenance mode).

- and a few other exciting projects you can explore on the redox-os group.

We also have some in-house tools, which are collections of small, useful command-line programs:

- extrautils - Extra utilities such as reminders, calendars, spellcheck, and so on.

- binutils - Utilities for working with binary files.

We also actively contribute to third-party projects that are heavily used in Redox.

- uutils/coreutils - Cross-platform Rust rewrite of the GNU Coreutils.

- smoltcp - The TCP/IP stack used by Redox.

What tools are fitting for the Redox distribution?

The necessary tools for a usable system, we offer variants with fewer programs.

The listed tools fall into three categories:

- Critical, which are needed for a full functioning and usable system.

- Ecosystem-friendly, which are there for establishing consistency within the ecosystem.

- Fun, which are "nice" to have and are inherently simple.

The first category should be obvious: an OS without certain core tools is a useless OS. The second category contains the tools which are likely to be non-default in the future, but nonetheless are in the official distribution right now, for the charm. The third category is there for convenience: namely for making sure that the Redox infrastructure is consistent and integrated.

Influences

This page explains how Redox was influenced by other operating systems.

(The list is ordered by influence level)

Minix

The most influential Unix-like system with a microkernel. It has advanced features such as system modularity, kernel panic resistence, driver reincarnation, protection against bad drivers and secure interfaces for process comunication.

Redox is largely influenced by Minix - it has a similar architecture but with a feature set written in Rust.

seL4

The most performant and simplest microkernel of the world.

Redox follow the same principle, trying to make the kernel-space small as possible (moving components to user-space and reducing the number of system calls, passing the complexity to user-space) and keeping the overall performance good (reducing the context switch cost).

Plan 9

This Bell Labs OS brings the concept of "Everything is a File" to the highest level, doing all the system communication from the filesystem.

Linux

The most advanced monolithic kernel and biggest open-source project of the world. It brought several improvements and optimizations to the Unix-like world.

Redox tries to implement the Linux performance improvements in a microkernel design.

BSD

This Unix family included several improvements on Unix systems and the open-source variants of BSD added many improvements to the original system (like Linux did).

-

FreeBSD - The Capsicum (a capability-based system) and jails (a sandbox technology) influenced the Redox namespaces implementation.

-

OpenBSD - The system call, filesystem, display server and audio server sandbox and others influenced the Redox security.

Hardware Support

There are billions of devices with hundreds of models and architectures in the world. We try to write drivers for the most used devices to support more people. Support depends on the specific hardware, since some drivers are device-specific and others are architecture-specific.

Have a look at the HARDWARE.md document to see all tested computers.

I have a low-end computer, would Redox work on it?

A CPU is the most complex machine of the world: even the oldest processors are powerful for some tasks but not for others.

The main problem with old computers is the amount of RAM available (they were sold in a era where RAM chips were expensive) and the lack of SSE/AVX extensions (programs use them to speed up the algorithms). Because of this some modern programs may not work or require a lot of RAM to perform complex tasks.

Redox itself will work normally if the processor architecture is supported by the system, but the performance and stability may vary per program.

Why CPUs older than i686 aren't supported?

- i686 (essentially Pentium II) introduced a wide range of features that are critical for the Redox kernel.

- It would be possible to go all the way back to i486, but that would make us lose nice functions like

fxsave/fxrstorand we would need to build userspace without any SSE code. - i386 has no atomics (at all) which makes it not likely as a target.

Compatibility Table

| Category | Items |

|---|---|

| CPU | - Intel 64-bit (x86_64) - Intel 32-bit (i686) from Pentium II and after with limitations - AMD 32/64-bit - ARM 64-bit (Aarch64) with limitations |

| Hardware Interfaces | - ACPI, PCI, USB |

| Storage | - IDE (PATA), SATA (AHCI), NVMe |

| Video | - BIOS VESA, UEFI GOP |

| Sound | - Intel, Realtek chipsets |

| Input | - PS/2 keyboards, mouse and touchpad - USB keyboards, mouse and touchpad |

| Ethernet | - Intel Gigabit and 10 Gigabit ethernet - Realtek ethernet |

Important Programs

This page covers important programs and libraries supported by Redox.

Redox is designed to be source-compatible with most Unix, Linux and POSIX-compliant applications, only requiring compilation.

Currently, most GUI applications require porting, as we don't support X11 or Wayland yet.

Some important software that Redox supports:

- GCC

- LLVM

- FFMPEG

- OpenSSL

- Mesa3D

- SDL2

- Git

- RustPython

- GNU Bash

You can see all Redox components and ported programs on the build server list.

Getting started

Redox is still at experimental/alpha stage, but there are many things that you can do with it, and it's fun to try it out. You can start by downloading and running the latest release. Read the instructions for running in a virtual machine or running on real hardware.

The Building Redox page has information about configuring your system to build Redox, which is necessary if you want to contribute to the development. The Advanced Podman Build page gives a look under the hood of the build process to help you maintain your build environment.

By reading the Build System page you can have a complete understanding of the build system.

Running Redox in a Virtual Machine

Download the bootable images

This section will guide you to download the Redox images.

(You need to use the harddrive.img image variant for QEMU or VirtualBox)

Stable Releases

The bootable images for the 0.9.0 release are located on the build server release folder. To try Redox using a virtual machine such as QEMU or VirtualBox, download the demo variant, check the SHA256 sum to ensure it has downloaded correctly.

sha256sum $HOME/Downloads/redox_demo_x86_64_*_harddrive.img.zst

If you have more than one demo image in the Downloads directory, you may need to replace the * symbol with the date of your file.

If the demo variant doesn't boot on your computer, try the desktop and server variants.

Even if the desktop and server variants doesn't work, use the daily images below.

Daily Images

If you want to test the latest Redox changes you can use our bootable images created each day by opening the build server images and downloading your preferred variant. Once the download is complete, check the SHA256 sum.

(Sometimes our daily images can be one week old or more because of breaking changes)

Decompression

The Redox images are compressed using the Zstd algorithm, to decompress follow the steps below:

Linux

GUI

- Install GNOME File Roller or KDE Ark (both can be installed from Flathub)

- Open the Redox image and click on the "Extract" button

If you are using the GNOME Nautilus or KDE Dolphin file manager, right-click the file and select the option to extract the file.

Terminal

Install the Zstd tool and run:

zstd -d $HOME/Downloads/redox_*_x86_64_*_harddrive.img.zst

Windows

GUI

- Install 7-Zip

- Right-click the Redox image, hover the 7-Zip section and click on the option to extract the file or open the file on 7-Zip and extract

VirtualBox Instructions

To run Redox in a VirtualBox virtual machine you need to do the following steps:

- Create a VM with 2048 MB of RAM memory (or less if using a simpler Redox image variant) and 32MB of VRAM (video memory)

- Enable Nested Paging

- Change the keyboard and mouse interface to PS/2

- Change the audio controller to Intel HDA

- Disable USB support

- Go to the network settings of the VM and change the NIC model to 82540EM

- Go to the storage settings of the VM, create an IDE controller and add the Redox bootable image on it

- Start the VM!

If you want to install Redox on the VM create a VDI disk of 5GB (or less if you are using a simplier Redox image variant).

Command for the pre-installed image

If you want to do this using the command-line, run the following commands:

-

VBoxManage createvm --name Redox --register -

VBoxManage modifyvm Redox --memory 2048 --vram 32 --nic1 nat --nictype1 82540EM \ --cableconnected1 on --usb off --keyboard ps2 --mouse ps2 --audiocontroller hda \ --audioout on --nestedpaging on -

VBoxManage convertfromraw $HOME/Downloads/redox_demo_x86_64_*_harddrive.img harddrive.vdi -

VBoxManage storagectl Redox --name SATA --add sata --bootable on --portcount 1 -

VBoxManage storageattach Redox --storagectl SATA --port 0 --device 0 --type hdd --medium harddrive.vdi -

VBoxManage startvm Redox

Command for the Live ISO image

If you want to use the Live ISO run the following commands:

-

VBoxManage createvm --name Redox --register -

VBoxManage modifyvm Redox --memory 2048 --vram 32 --nic1 nat --nictype1 82540EM \ --cableconnected1 on --usb off --keyboard ps2 --mouse ps2 --audiocontroller hda \ --audioout on --nestedpaging on -

VBoxManage storagectl Redox --name SATA --add sata --bootable on --portcount 1 -

VBoxManage storageattach Redox --storagectl SATA --port 0 --device 0 --type dvddrive --medium $HOME/Downloads/redox_demo_x86_64_*_livedisk.iso -

VBoxManage startvm Redox

QEMU Instructions

Linux

You can then run the image in your preferred emulator. If you don't have an emulator installed, use the following command (Pop!_OS/Ubuntu/Debian) to install QEMU:

sudo apt-get install qemu-system-x86

This command will run QEMU with various Redox-compatible features enabled:

SDL_VIDEO_X11_DGAMOUSE=0 qemu-system-x86_64 -d cpu_reset,guest_errors -smp 4 -m 2048 \

-chardev stdio,id=debug,signal=off,mux=on,"" -serial chardev:debug -mon chardev=debug \

-machine q35 -device ich9-intel-hda -device hda-duplex -netdev user,id=net0 \

-device e1000,netdev=net0 -device nec-usb-xhci,id=xhci -enable-kvm -cpu host \

-drive file=`echo $HOME/Downloads/redox_demo_x86_64_*_harddrive.img`,format=raw

💡 Tip: if you encounter an error with the file name, verify that the name passed into the previous command (i.e.,

$HOME/Downloads/redox_demo_x86_64_*_harddrive.img) matches the file you downloaded.

MacOSX Instructions (Intel)

To install QEMU on MacOSX, use the following command:

brew install qemu

📝 Note: The

brewcommand is part of the Homebrew package manager for macOS.

This command will run QEMU with various Redox-compatible features enabled:

SDL_VIDEO_X11_DGAMOUSE=0 qemu-system-x86_64 -d cpu_reset,guest_errors -smp 4 -m 2048 \

-chardev stdio,id=debug,signal=off,mux=on,"" -serial chardev:debug -mon chardev=debug \

-machine q35 -device ich9-intel-hda -device hda-duplex -netdev user,id=net0 \

-device e1000,netdev=net0 -device nec-usb-xhci,id=xhci -cpu max \

-drive file=`echo $HOME/Downloads/redox_demo_x86_64_*_harddrive.img`,format=raw

💡 Tip: if you encounter an error with the file name, verify that the name passed into the previous command (i.e.,

$HOME/Downloads/redox_demo_x86_64_*_harddrive.img) matches the file you downloaded.

Windows

To install QEMU on Windows, follow the instructions here. The installation of QEMU will probably not update your command path, so the necessary QEMU command needs to be specified using its full path. Or, you can add the installation folder to your PATH environment variable if you will be using it regularly.

Following the instructions for Linux above, download the same redox_demo image. Then, in a Command window, cd to the location of the downloaded Redox image and run the following very long command:

"C:\Program Files\qemu\qemu-system-x86_64.exe" -d cpu_reset,guest_errors -smp 4 -m 2048 -chardev stdio,id=debug,signal=off,mux=on,"" -serial chardev:debug -mon chardev=debug -machine q35 -device ich9-intel-hda -device hda-duplex -netdev user,id=net0 -device e1000,netdev=net0 -device nec-usb-xhci,id=xhci -drive file=redox_demo_x86_64_2022-11-23_638_harddrive.img,format=raw

💡 Tip: if you get a filename error, change

redox_demo_x86_64_*_harddrive.imgto the name of the file you downloaded.

💡 Tip: if necessary, change

"C:\Program Files\qemu\qemu-system-x86_64.exe"to reflect where QEMU was installed. The quotes are needed if the path contains spaces.

Using the QEMU emulation

As the system boots, it will ask you for a screen resolution to use, for example 1024x768. After selecting a screen size, the system will complete the boot, start the Orbital GUI, and display a Redox login screen. Login as user user with no password. The password for root is password. Use Ctrl+Alt+G to toggle the mouse behavior if you need to zoom out or exit the emulation. If your emulated cursor is out of alignment with your mouse position, type Ctrl+Alt+G to regain full cursor control, then click on your emulated cursor. Ctrl+Alt+F toggles between full screen and window views.

See Trying Out Redox for things to try.

If you want to try Redox in server mode, add -nographic -vga none to the command line above. You may wish to switch to the redox_server edition. There are also i686 editions available, although these are not part of the release.

Running Redox on Real Hardware

(You need to use the *livedisk.iso image variant for real hardware)

Since version 0.8.0, Redox can now be installed on certain hard drives and internal SSDs, including some vintage systems. USB devices are not yet supported during run-time, although they can be used for installation and livedisk boot. Check the release notes for additional details on supported hardware. Systems with unsupported devices can still use the livedisk method described below. Ensure you backup your data before trying Redox on your hardware.

Hardware support is limited at the moment, so your milage may vary. Only USB input devices (HID) work. There is a PS/2 driver, which works with the keyboards and touchpads in many (but not all) laptops. For networking, the Realtek and Intel ethernet controllers are currently supported.

On some computers, hardware incompatibilities, e.g. disk driver issues, can slow down Redox performance. This is not reflective of Redox in general, so if you find that Redox is slow on your computer, please try it on a different model for a better experience.

The current ISO image uses a bootloader to load the filesystem into memory (livedisk) and emulates a hard drive. You can use the system in this mode without installing. Although its use of memory is inefficient, it is fully functional and does not require changes to your device. The ISO image is a great way to try out Redox on real hardware.

Creating a Bootable USB Drive

Download an Compressed ISO Image

You can obtain a livedisk ISO image either by downloading the latest release, or by building one. The demo ISO is recommended for most laptops. After downloading completes, check the SHA256 sum:

sha256sum $HOME/Downloads/redox_demo_x86_64_*_livedisk.iso.zst

If you have more than one demo image in the Downloads directory, you may need to replace the * symbol with the date of your file.

If the demo variant doesn't boot on your computer, try the desktop and server variants.

If even the desktop and server variants don't work, use the daily images below.

Daily Images

If you want to test the latest Redox changes you can use our bootable images created each day by opening the build server images and downloading your preferred variant.

(Sometimes our daily images can be one week old or more because of breaking changes) Once the download is complete, check the SHA256 sum.

Decompress the ISO Image

Downloaded Redox images are compressed using the Zstd algorithm. To decompress an image, follow the appropriate steps below for your system:

Linux (GUI)

- Install GNOME File Roller or KDE Ark (both can be installed from Flathub)

- Open the Redox image and click on the "Extract" button

If you are using the GNOME Nautilus or KDE Dolphin file manager, right-click the file and select the option to extract the file.

Linux (Terminal)

Install the Zstd tool and run:

zstd -d $HOME/Downloads/redox_*_x86_64_*_livedisk.iso.zst

Windows (GUI)

- Install 7-Zip

- Right-click the Redox image, hover the 7-Zip section and click on the option to extract the file or open the file on 7-Zip and extract

Flash the ISO Image

Linux Instructions

We recommend using the Popsicle tool to flash ISO images to USB devices on Linux. To flash an image, follow the steps below:

- Open the Releases section to open the Popsicle releases page and download the

.AppImagefile. - Open your file manager, click with the right-button of your mouse on the

.AppImagefile and open the "Properties", find the "Permissions" section and mark it as executable. - Open the Popsicle

.AppImagefile, select the downloaded Redox image and your USB device. - Confirm the flash process and wait until the progress bar reach 100%. If the flashing process completes with no errors, the flash was successful.

You can now restart your Linux machine and boot into Redox.

Windows Instructions

We recommend using the balenaEtcher tool on Windows to flash your USB device, follow the steps below:

- Open the balenaEtcher website, click on the "Download Etcher" button and download the "Etcher for Windows" asset.

- Install and open balenaEtcher, select the ISO image of Redox, select the USB device and click on "Flash!"

- Confirm the permission to erase the data of your device and wait until the progress bar reach 100%

Now you can now restart your Windows system and boot into Redox.

Booting the System

Some computers don't come with USB booting enabled, to enable it press the keyboard key to open your UEFI or BIOS setup and allow the booting from USB devices (the name varies from firmware to firmware).

If you don't know the keyboard keys to open your UEFI/BIOS setup or boot menu, press the Esc or F keys (from 1 until 12), if you press the wrong key or got the wrong timing, don't stop your operating system boot process to try again, as it could corrupt your data.

Once the ISO image boots, the system will display the Orbital GUI. Log in as the user named user with no password. The password for root is password.

See Trying Out Redox for things to try.

To switch between Orbital and the console, use the following keys:

- F1: Display the console log messages

- F2: Open a text-only terminal

- F3: Return to the Orbital GUI

If you want to be able to boot Redox from your HDD or SSD, follow the Installation instructions.

Redox isn't currently going to replace your existing operating system, but testing is important to help us fix bugs and add features: boot Redox on your computer, and see what works.

Installing Redox on a Drive

Once you have downloaded or built your ISO image, you can install it to your internal HDD or SSD. Please back up your system before attempting to install. Note that at this time (Release 0.8.0), you can't install onto a USB device, or use a USB device for your Redox filesystem, but you can install from it.

After starting your livedisk system from a USB device or from CD/DVD, log in as the user named user with an empty password. Open a terminal window and type:

sudo redox_installer_tui

If Redox recognizes your device, it will prompt you to select a device to install on. Choose carefully, as it will erase all the data on that device. Note that if your device is not recognized, it may offer you the option to install on disk/live (the in-memory livedisk). Don't do this, as it will crash Redox.

You will be prompted for a redoxfs password. This is for a encrypted filesystem. Leave the password empty and press Enter if an encrypted filesystem is not required.

Once the installation completes, power off your computer, remove the USB device, power on your computer and you are ready to start using Redox!

Trying Out Redox

There are several programs, games, demos and other things to try on Redox. Most of these are not included in the regular Redox build, so you will need to run the demo variant from the list of available Redox images. Currently, Redox does not have Wi-Fi support, so if you need Wi-Fi for some of the things you want to do, you are best to use an Ethernet cable or run Redox in a virtual machine. Most of the suggestions below do not require Internet access.

On the demo variant, click on the Redox symbol in the bottom left corner of the screen. This brings up a menu, which, for the demo variant, includes some games. Feel free to give them a try!

Many of the available commands are in the folders /usr/bin and /ui/bin, which are included in your command path. Open a Terminal window and type ls /usr/bin (or ls /scheme/file/usr/bin) to see some of the available commands.

💡 Note: some of the games listed below are installed in the

/usr/gamesdirectory, which is not detected in the terminal shell by default. To run these games from the terminal, you may have to specify the path of their executables.

Programs

FFMPEG

The most advanced multimedia library of the world.

- Run the following command to play an audio file:

ffplay music-name.mp3

(Change the audio format according to your file)

- Run the following command to play a video file:

ffplay video-name.mp4

(Change the video format according to your file)

COSMIC Files

An advanced file manager written in Rust, similar to GNOME Nautilus or Files.

COSMIC Editor

An advanced text editor written in Rust, similar to KDE KWrite.

Git

Git is a tool used for source code management.

- Run the following command to download a Git repository:

git clone repository-link

(Replace the "repository-link" part with your repository URL)

RustPython

RustPython is a Python 3.11+ interpreter written in Rust.

- Run the following command to run your Python script:

rustpython script-name.py

(The PyPI dependency manager is supported)

Periodic Table

The Periodic Table /usr/bin/periodictable is a demonstration of the OrbTk user interface toolkit.

Sodium

Sodium is Redox's Vi-like editor. To try it out, run the sodium command from a terminal.

A short list of the Sodium defaults:

| Keys | Function |

|---|---|

h, j, k, l | Navigation keys |

i, a | Enter "Insert" mode |

; | Enter "Prompt" mode |

shift-space | Enter "Normal" mode |

For a more extensive list, run :help from within Sodium.

Rusthello

Rusthello is an advanced Reversi AI, made by HenryTheCat. It is highly concurrent, so this acts as a demonstration of Redox's multithreading capabilities. It supports various AIs, such as brute force, minimax, local optimizations, and hybrid AIs.

In a Terminal window, type rusthello.

Then you will get prompted for various things, such as difficulty, AI setup, and so on. When this is done, Rusthello interactively starts the battle between you and an AI or an AI and an AI.

Games

Freedoom

Freedoom is a first-person shooter in the form of content for a Doom engine. For Redox, we have included the PrBoom engine to run Freedoom. You can read more about Freedoom on the Freedoom website. PrBoom can be found on the PrBoom website.

Freedoom can be run by selecting its entry from the "Games" section of the Orbital system menu, or by running either /usr/games/freedoom1 or /usr/games/freedoom2 from a terminal.

Hit Esc and use the arrow keys to select Options->Setup->Key Bindings for keyboard help.

Neverball and Nevergolf

Neverball and Nevergolf are 3D pinball and golf games, respectively. Both can be run from the Orbital system menu, under "Games".

Sopwith

Sopwith is a game which allows players to pilot a small, virtual plane. The original game was written in 1984 and used PC graphics, but it is now presented to users using the SDL library. To play it, run the sopwith command from a terminal.

| Control Key | Description |

|---|---|

Comma (,) | Pull back |

Slash (/) | Push forward |

Dot (.) | Flip aircraft |

| Space | Fire gun |

b | Drop bomb |

Syobon Action

Syobon Action is 2D side-scrolling platformer that you won't enjoy. To play it, run syobonaction from a terminal window. It's recommended that you read the GitHub page so you don't blame us.

Terminal Games Written in Rust

Also check out some games that have been written in Rust, and use the Terminal Window for simple graphics. In a Terminal window, enter one of the following commands:

baduk- Baduk/Godem- Democracyflappy- Flappy Bird cloneice- Ice Sliding Puzzleminesweeper- Minesweeper but it wrapsreblox- Tetris-like falling blocksredoku- Sudokusnake- Snake

Building Redox

Congrats on making it this far! Now you will build Redox. This process is for x86-64 machines (Intel/AMD). There are also similar processes for i686 and AArch64/ARM64.

The build process fetches files from the Redox Gitlab server. From time to time, errors may occur which may result in you being asked to provide a username and password during the build process. If this happens, first check for typos in the git URL. If that doesn't solve the problem and you don't have a Redox GitLab login, try again later, and if it continues to happen, you can let us know through the chat.

To avoid bugs from different build environments (operating systems) we are using Rootless Podman for major parts of the build. Podman is invoked automatically and transparently within the Makefiles.

The TL;DR version is here. More details are available in the Advanced Podman Build page.

You can find out more about Podman on the Podman documentation.

(Don't forget to read the Build System page to know our build system organization and how it works)

Podman Build Overview

Podman is a container manager that creates containers to execute a Linux distribution image. In our case, we are creating an Debian image, with a Rust installation and all the dependencies needed to build the system and programs.

The build process is performed in your normal working directory, e.g., ~/tryredox/redox. Compilation of the Redox components is performed in the container, but the final Redox image (build/$ARCH/$CONFIG/harddrive.img or build/$ARCH/$CONFIG/livedisk.iso) is constructed using FUSE running directly on your host machine.

Setting PODMAN_BUILD to 1 in .config, on the make command line (e.g., make PODMAN_BUILD=1 all) or in the environment (e.g., export PODMAN_BUILD=1; make all) will enable Podman.

First, a base image called redox_base will be constructed, with all the necessary packages for the build system. A "home" directory will also be created in build/podman. This is the home directory of your container alter ego, poduser. It will contain the rustup install, and the .bashrc. This takes some time, but is only done when necessary. The tag file build/container.tag is also created at this time to prevent unnecessary image builds.

Then, various make commands are executed in containers built from the base image. The files are constructed in your working directory tree, just as they would for a non-Podman build. In fact, if all necessary packages are installed on your host system, you can switch Podman on and off relatively seamlessly, although there is no benefit of doing so.

The build process is using Podman's keep-id feature, which allows your regular User ID to be mapped to poduser in the container. The first time a container is built, it takes some time to set up this mapping. After the first container is built, new containers can be built almost instantly.

TL;DR - New or Existing Working Directory

New Working Directory

If you have already read the Building Redox instructions, but you wish to use Podman Build, follow these steps:

-

Ensure you have the

curlprogram installed. e.g., for Pop!_OS/Ubuntu/Debian:which curl || sudo apt-get install curl -

Create a new directory and run

podman_bootstrap.shinside of it. This will clone the repository and install Podman.mkdir -p ~/tryredoxcd ~/tryredoxcurl -sf https://gitlab.redox-os.org/redox-os/redox/raw/master/podman_bootstrap.sh -o podman_bootstrap.shtime bash -e podman_bootstrap.shYou may be asked which QEMU installation you want. Please select

full.You may be asked which Podman container runtime you want to use,

crunorrunc. Choosecrun, butruncwill also work. -

Update your path to include

cargoand the Rust compiler.source ~/.cargo/env -

Navigate to the

redoxdirectory.cd ~/tryredox/redox -

Build the system. This will take some time.

time make all

- If the command ask your to choose an image repository select the first item, it will give an error and you need to run the

time make allcommand again

Existing Working Directory

If you already have the build system, simply perform the following steps:

-

Change to your working directory

cd ~/tryredox/redox -

Update the build system and wipe all binaries

make pull clean -

Install Podman. If your Linux distribution is not supported, check the installation instructions to determine which dependencies are needed. Or, run the following in your

redoxbase` directory:./podman_bootstrap.sh -d -

Enable Podman.

nano .configPODMAN_BUILD?=1📝 Note: the initial container setup for the Podman build can take 15 minutes or more, but it is comparable in speed to native build after that.

-

Build the Redox image.

make all

Run in a virtual machine

You can immediately run the new image (build/x86_64/desktop/harddrive.img) in a virtual machine with the following command:

make qemu

📝 Note: if you are building the system using

build.shto change the CPU architecture or filesystem contents, you can also provide theqemuoption to run the virtual machine:./build.sh -a i686 -c demo qemuThis will build

build/i686/demo/harddrive.img(if it doesn't already exist) and run it in the QEMU emulator.

The emulator will display the Redox GUI (Orbital). See Using the emulation for general instructions and Trying out Redox for things to try.

Run without a GUI

To run the virtual machine without a GUI, use:

make qemu gpu=no

If you want to capture the terminal output, read the Debug Methods section.

💡 Tip: if you encounter problems running the virtual machine, try turning off various virtualization features with

make qemu kvm=noormake qemu iommu=no. These same arguments can also be used withbuild.sh.

QEMU Tap For Network Testing

Expose Redox to other computers within a LAN. Configure QEMU with a "TAP" which will allow other computers to test Redox client/server/networking capabilities.

Please join the chat if this is something you are interested in pursuing.

Building A Redox Bootable Image

Read the Testing on Real Hardware section.

Contributor Note

If you intend to contribute to Redox or its subprojects, please read the CONTRIBUTING document to understand how the Redox build system works, and how to set up your repository fork appropriately. You can use ./bootstrap.sh -d in the redox folder to install the prerequisite packages if you have already done a git clone of the sources.

If you encounter any bugs, errors, obstructions, or other annoying things, please join the chat or report the issue to the build system repository or a proper repository for the component. Thanks!

build.sh

build.sh is a shell script for quickly invoking make for a specified variant, CPU architecture, and output file.

💡 Tip: for doing Redox development, such settings should usually be configured in the

.configfile (see the Configuration Settings page). But for users who are just trying things out, thebuild.shscript can be used to runmakefor you.

Example 1

The following builds the server variant of Redox for the i686 (32-bit Intel/AMD) CPU architecture (defined in config/i686/server.toml):

./build.sh -a i686 -c server live

The resulting image is build/i686/server/livedisk.iso, which can be used to install Redox from a USB device.

Example 2

The following builds the desktop variant of Redox for the aarch64 (64-bit ARM) CPU architecture (defined in config/aarch64/desktop.toml).

./build.sh -f config/aarch64/desktop.toml qemu

The resulting image is build/aarch64/desktop/harddrive.img, which is then run in the QEMU emulator upon completion of the build.

💡 Tip: if you are going to use

build.shrepeatedly, it's recommended that you do so consistently. The script's underlyingmakecommand doesn't keep any record of the build settings used betweenbuild.shruns.

Details of build.sh and other settings are described in the Configuration Settings page.

Native Build

This page explains how to build Redox in your operating system's native environment. Keep in mind that it's possible to encounter issues with the native build that don't occur with the Podman build, so this method is only recommended where Podman cannot be used.

📝 Note: be sure to read the Build System page for an explanation of the build system's organization and functionality.

Supported Unix-like Distributions and Podman Build

The following Unix-like systems are supported:

- Pop_OS!

- Ubuntu

- Debian

- Fedora

- Arch Linux

- OpenSUSE

- Gentoo (basic support)

- FreeBSD

- MacOSX (require workarounds)

- Nix (under development)

- Solus (basic support, not maintained)

If you encounter a weird or difficult-to-fix problem, test the Podman Build to determine if the problem occurs there as well.

Preparing the Build

Bootstrap Prerequisites and Fetch Sources

On supported Linux distributions, build system preparation can be performed automatically via the build system's bootstrap script:

-

Ensure you have the

curlprogram installed. e.g., for Pop!_OS/Ubuntu/Debian:which curl || sudo apt-get install curl -

Create a new directory and run the

native_bootstrap.shscript in it.mkdir -p ~/tryredoxcd ~/tryredoxcurl -sf https://gitlab.redox-os.org/redox-os/redox/raw/master/native_bootstrap.sh -o native_bootstrap.shtime bash -e native_bootstrap.shYou will be asked to confirm some steps: answer with

yor1.For an explanation of what the

native_bootstrap.shscript does, read this section.Note that

curl -sfoperates silently, so if there are errors, you may get an empty or incorrect version ofnative_bootstrap.sh. Check for typos in the command and try again. If you continue to have problems, join the chat and let us know.Please be patient. The bootstrapping process can take anywhere from 5 minutes to an hour depending on the hardware and network it's being run on.

-

After bootstrapping is completed, update the

PATHenvironment variable for the current shell:source ~/.cargo/env

Setting Configuration Values

The build system uses several configuration files, which contain settings that you may wish to change. These are detailed in the Configuration Settings page. By default the build system cross-compile to the x86_64 CPU architecture, using the desktop configuration (at config/x86_64/desktop.toml). Set the desired ARCH and CONFIG_FILE in .config.

The build.sh script also allows the user to specify the CPU architecture and filesystem contents to be used in the build, although these settings be re-specified every time the script is run.

Compiling Redox

At this point we have:

- Downloaded the sources

- Tweaked the settings to our liking

- Probably added our recipe to the filesystem

We are ready to build the Redox operating system image. Skip ahead to Configuration Settings if you want to build for a different CPU architecture or with different filesystem contents.

Build all system components and programs

To build all the components and packages to be included in the filesystem.

cd ~/tryredox/redox

time make all

This will build the target build/x86_64/desktop/harddrive.img, which can be run in a virtual machine.

Give it a while. Redox is big. Read the make all (first run) section for an explanation of what the make all command does.

💡 Tip: the filesystem parts are merged into the final system image using the FUSE library. The

bootstrap.shscript installslibfuseautomatically. If you encounter problems with the final Redox image, verifylibfuseis installed and that you are able to use it.

From Nothing To Hello World

This page describes the quickest way to test a program on Redox. This tutorial doesn't build Redox from source.

In this example we will use a "Hello World" program written in Rust.

-

Create the

tryredoxfolder.mkdir -p ~/tryredox -

Navigate to the

tryredoxfolder.cd ~/tryredox -

Download the script to bootstrap Podman and download the Redox build system.

curl -sf https://gitlab.redox-os.org/redox-os/redox/raw/master/podman_bootstrap.sh -o podman_bootstrap.sh -

Execute the downloaded script.

time bash -e podman_bootstrap.sh -

Enable the Rust toolchain in the current shell.

source ~/.cargo/env -

Navigate to the Redox build system directory.

cd ~/tryredox/redox -

Create the

.configfile and add theREPO_BINARYenvironment variable to enable the binary-mode.echo "REPO_BINARY?=1 \n CONFIG_NAME?=my_config" >> .config -

Create the

hello-worldrecipe folder.mkdir cookbook/recipes/other/hello-world -

Create the

sourcefolder for the recipe.mkdir cookbook/recipes/other/hello-world/source -

Navigate to the recipe's

sourcefolder.cd cookbook/recipes/other/hello-world/source -

Initialize a Cargo project with the "Hello World" string.

cargo init --name="hello-world" -

Create the

hello-worldrecipe configuration.cd ~/tryredox/redoxnano cookbook/recipes/other/hello-world/recipe.toml -

Add the following to the recipe configuration:

[build] template = "cargo" -

Create the

my_configfilesystem configuration.cp config/x86_64/desktop.toml config/x86_64/my_config.toml -

Open the

my_configfilesystem configuration file (i.e.,config/x86_64/my_config.toml) and add thehello-worldpackage to it.[packages] # Add the item below hello-world = "source" -

Build the Hello World program and the Redox image.

time make prefix r.hello-world image -

Start the Redox virtual machine without a GUI.

make qemu gpu=no -

At the Redox login screen, write "user" for the user name and press Enter.

-

Run the "Hello World" program.

helloworld -

Shut down the Redox virtual machine.

sudo shutdown

Configuration Settings

The Redox build system applies configuration settings from various places to determine the final Redox image. Most of these settings ultimately come from the build system's environment variables (or similarly-named Make variables) and the contents of the chosen filesystem configuration file.

Environment Variables

The default values for the build system's environment variables are mostly defined in the mk directory—particularly in mk/config.mk. Local changes from the default values, however, should be applied in the .config file, or temporarily on the make command line.

Three important variables of interest are ARCH, CONFIG_NAME, and FILESYSTEM_CONFIG, as they specify the system to be built. These, and other important environment variables, can be seen in the following table:

| Variable | Definition |

|---|---|

ARCH | Specifies the CPU architecture that the system is to be built for. The default is x86_64. |

CONFIG_NAME | Determines the name of the filesystem configuration, and is normally used to construct the FILESYSTEM_CONFIG name (the desktop variant is used by default). |

FILESYSTEM_CONFIG | Determines the filesystem configuration file location. See the Filesystem Configuration section below. The default is config/$ARCH/$CONFIG_NAME.toml, but this can be changed if the desired configuration file is in a different location. |

BOARD | For single board computers such as Raspberry Pi 3B+ that require special configuration, $ARCH/$BOARD is used in place of $ARCH. Defaults to empty. |

QEMU_MEM | Sets the QEMU RAM memory quantity, e.g., QEMU_MEM=2048. |

QEMU_SMP | Sets the QEMU CPU core quantity, e.g., QEMU_SMP=4. |

PREFIX_BINARY | If set to 0 (PREFIX_BINARY?=0), the build system will enable the toolchain compilation and will not download the toolchain binaries from the Redox build server. |

REPO_BINARY | If set to 1 (REPO_BINARY?=1), the build system will download/install pre-built packages from the Redox package server by default, rather than build them from source (i.e., recipes). |

FILESYSTEM_SIZE | The size in MB of the filesystem contained in the final Redox image. See the Filesystem Size section before changing it. |

REDOXFS_MKFS_FLAGS | Flags to the program that builds the Redox filesystem. The --encrypt option enables disk encryption. |

PODMAN_BUILD | If set to 0 (PODMAN_BUILD?=0), the build system will use the build environment from your Linux distribution or Unix-like system instead of Podman. See the Native Build page for more information. |

CONTAINERFILE | The Podman container configuration file. See the Podman Build page for more information. |

PREFER_STATIC | If set to 1 (PREFER_STATIC?=1), all packages will be statically linked. By default, a package will be dynamically linked if it supports it.💡 Tip: if this was previously unset, a full recompilation of the sysroot folder will be required. |

The Redox image that is built is typically named build/$ARCH/$CONFIG_NAME/harddrive.img or build/$ARCH/$CONFIG/livedisk.iso.

.config

The purpose of the .config file is to allow default configuration settings to be changed without explicitly setting those changes in every make command (or modifying the contents of the mk directory). The file is also included in the .gitignore list to ensure it won't be committed by accident.

To permanently override the settings in the mk/config.mk section, add a .config file to the redox base directory (i.e., where make commands are run) and set the overriding values in that file.

For example, the following configuration specifies the desktop-minimal image variant will be built for the i686 CPU architecture. These settings will be applied implictly to all subsequent make commands:

ARCH?=i686

CONFIG_NAME?=desktop-minimal

📝 Note: Any QEMU option can be inserted 📝 Note: if

podman_bootstrap.shwas run previously, the.configfile may already exist. 💡 Tip: when adding environment variables in the.configfile, don't forget the?symbol at the end of variable names. This allows the variable to be overridden on the command line or in the environment. In particular,PODMAN_BUILD?=1must include the question mark to function correctly.

Changing the QEMU CPU Core and Memory Quantity

For example, to change the CPU core and RAM memory quantities used when running the Redox image in QEMU, add the following environment variables to your .config file:

QEMU_SMP?=<number-of-threads>

QEMU_MEM?=<number-in-mb>

Command Line

The default settings in mk/config.mk can be manually overridden by explicitly setting them on the make command line.

For example, the following command builds the demo image variant and loads it into QEMU:

make CONFIG_NAME=demo qemu

Some environment variables can also be set for the lifetime of the current shell by setting them at the command line:

export ARCH=i686; make all

Overriding settings in this way is only temporary, however. Additionally, for those using the Podman Build, some settings may be ignored when using this method. For best results, use .config.

mk/config.mk

The Redox build system uses several Makefiles, most of which are in the mk directory. Most settings of interest have have been grouped together in mk/config.mk.

Feel free to open mk/config.mk in your favorite editor and have a look through it; just be sure not to apply any changes:

nano mk/config.mk

The mk/config.mk file should never be modified directly, especially if you are contributing to the Redox project, as doing so could create conflicts in the make pull command.

To apply lasting changes to environment variables, please refer to the .config section. To apply changes only temporarily, see the Command Line section.

build.sh

The build.sh script allows you to easily set ARCH, FILESYSTEM_CONFIG and CONFIG_NAME when running make. If you are not changing the values very often, it is recommended that you set the values in .config rather than use build.sh. But if you are testing against different CPU architectures or configurations, this script can help minimize effort, errors and confusion.

./build.sh [-a <ARCH>] [-c <CONFIG_NAME>] [-f <FILESYSTEM_CONFIG>] <TARGET> ...

The TARGET parameter may be any valid make target, although the recommended target is qemu. Additional variable settings may also be included, such as gpu=no

| Option | Description |

|---|---|

-a <ARCH> | The CPU architecture you are building for, x86_64, i686 or aarch64. Uppercase options -X, -6 and -A can be used as shorthands for -a x86_64, -a i686, and -a aarch64, respectively. |

-c <CONFIG_NAME> | The name of the filesystem configuration which appears in the name of the image being built. |

-f <FILESYSTEM_CONFIG> | Determines the filesystem configuration file location, which can be in any location but is normally in directory config/$ARCH.📝 Note: If you do specify -f <FILESYSTEM_CONFIG>, but not -a or -c, the file path determines the other values. Normally the file would be located at e.g., config/x86_64/desktop.toml. ARCH is determined from the second-to-last element of the path. If the second last element is not a known ARCH value, you must specify -a ARCH. CONFIG_NAME is determined from the basename of the file. |

The default value of FILESYSTEM_CONFIG is constructed from ARCH and CONFIG_NAME: config/$ARCH/$CONFIG_NAME.toml.

The default values for ARCH and CONFIG_NAME are x86_64 and desktop, respectively. These produce a default FILESYSTEM_CONFIG value of config/x86_64/desktop.toml.

Filesystem Configuration

The packages to be included in the final Redox image are determined by the chosen filesystem configuration file, which is a .toml file (e.g., config/x86_64/desktop.toml). Open desktop.toml and have a look through it:

nano config/x86_64/desktop.toml

For each supported CPU architecture, there are some filesystem configurations to choose from. For x86_64, there are desktop, demo and server configurations, as well as a few others. For i686, there are also some stripped down configurations for embedded devices or legacy systems with minimal RAM. Feel free to browse the config/x86_64 directory for more examples.

For more details on the filesystem configuration, and how to add additional packages to the build image, please see the Including Programs in Redox page.

Feel free to create your own filesystem configuration.

Architecture Names

The Redox build system supports cross-compilation to other CPU architectures. The CPU architecture that Redox is built for (specified by the ARCH environment variable) usually determines the filesystem configuration file that will be used by the build system.

See the currently supported CPU architectures by Redox below:

| CPU Architecture | Other Aliases |

|---|---|

i686 | x86 (32-bit), IA32 , x86 |

x86_64 | x86 (64-bit), x86-64, amd64, x64 |

aarch64 | ARM (64-bit), ARMv8, ARM64 |

riscv64gc | RISC-V (64-bit) |

The filesystem configurations for a given CPU architecture can be found in the config folder's correspondingly named sub-directory (e.g. config/x86_64).

Filesystem Size

The filesystem size is the total amount of storage space allocated for the filesystem that is built into the image, including all programs. It is specified in Megabytes (MB). The typical size is 512MB, although some configs (e.g., demo) are larger. The filesystem must be large enough to accommodate the packages included in the filesystem. For a livedisk system, the filesystem must not exceed the size of your system's RAM, and must also leave room for the package's installation and system execution.

The filesystem size is normally set from the filesystem configuration file, e.g. config/x86_64/demo.toml.

[general]

...

filesystem_size = 768

...

To change this, it is recommended that you create your own filesystem configuration and apply changes there. However, this can be temporarily overridden on the make command line, e.g.:

make FILESYSTEM_SIZE=512 image qemu

⚠️ Warning: setting the

filesystem_sizevalue too low will produce an error resembling the following:thread 'main' panicked at src/lib.rs:94:53: called `Result::unwrap()` on an `Err` value: Error(Path("/tmp/redox_installer_759506/include/openssl/.pkgar.srtp.h"), State { next_error: Some(Os { code: 28, kind: StorageFull, message: "No space left on device" }), backtrace: InternalBacktrace { backtrace: None } })

Filesystem Customization

The Redox image can be customized by tweaking the configuration files at config/your-cpu/*.toml. However, it is recommended that you create your own configuration file and apply changes there.

(The configuration files at config/your-cpu can override the data type values from the filesystem templates at config)

Creating a custom filesystem configuration

The following items describe the process for creating a custom filesystem configuration file (my_desktop.toml):

-

Create the

my_desktop.tomlfile from an existing filesystem configuration:cp config/your-cpu-arch/desktop.toml config/your-cpu-arch/my_desktop.toml -

Add the following to the

.configfile to set the new configuration as the build system's default:CONFIG_NAME?=my_desktop

Many filesystem configuration settings can be adjusted. See the templates in the config folder for reference.

💡 Tip: files named with the prefix "

my_" in theredoxrepo are git-ignored. Be sure to follow this convention for all custom filesystem configurations to avoid accidentally committing them to the Redox project.

Adding a package to the filesystem configuration

In the following example, the acid package is added to the my_desktop.toml configuration:

-

Open the

my_desktop.tomlfile:nano config/your-cpu/my_desktop.toml -

Add the

acidpackage to the[packages]section:[packages] acid = {} -

Build the

acidpackage and create a new Redox image:make r.acid image

Done! The acid package is now included in your new Redox image.

Binary Packages

By default, the Redox build system builds all packages from source (i.e., recipes). If you want to use pre-built packages from our build server, however, there's a TOML option for it.

This is useful for some purposes, such as producing development builds, confirming package status from the Redox package server, and reducing image build time with large programs.

-

Open the

my_desktop.tomlfile:nano config/your-cpu/my_desktop.toml -

Add the binary package below the

[packages]section:[packages] ... new-package = "binary" ... -

Download and add the binary package on your Redox image:

make image -

Open QEMU to verify your binary package:

make qemu

REPO_BINARY

In the previous example, the build system's default behavior was overridden by explicitly setting a package to use a pre-built binary. To configure the build system to download pre-built packages by default, however, we can set the REPO_BINARY environment variable (REPO_BINARY?=1).

When REPO_BINARY is enabled, the Redox image is made to use pre-built binaries for all packages assigned to {}; when REPO_BINARY is disabled, however, those same packages are compiled from source (i.e., recipes).

For example:

[packages]

...

package-name1 = {} # use the REPO_BINARY setting ("source" if 0; "binary" if 1)

package-name2 = "binary" # pre-built package

package-name3 = "source" # source-based recipe

...

Package Management

Redox package management is similar to that of the major Linux distributions, except that many of Redox's (Rust-written) packages use static linking by default, rather than dynamic linking.

Static linking provides a few advantages over dynamic linking:

-

Better Security

Static linking can improve system security by running each program's library code in isolated memory locations. This is true even when identical versions of a vulnerable library are being used by multiple programs at once.

To steal sensitive data from statically linked programs, an attacker would need to inject code directly into each program's memory address space, rather than the address space of a shared library. This increases the cost of the attack.

-

Better Performance

When a program is built with static linking, its library references are resolved before execution. Thus, there's no need for processing on the dynamic linker.

This means a statically linked program will open faster than its dynamically linked equivalent, provided both are loaded entirely from disk.

-

Simpler Dependency Management

When a dynamically linked program depends on multiple versions of the same library, naming conflicts can arise from the identical object or symbol names within those versions. This issue can necessitate isolating the library files, often by giving them unique names or placing them in separate

/libdirectories, to ensure the proper version is used in each case.With static linking, however, there's no need for run-time dependency management, as library dependencies are included within the executable binaries.

Rust programs aren't affected by this problem because of Cargo.

📝 Note: Rust programs are statically linked by default.

Format

What is "pkgar" ?

Short for "package archive", pkgar is a file format, library, and command-line

executable for creating and extracting cryptographically secure collections of

files, primarily for use in package management on Redox OS.

The technical details are still in development, so we think it is good to

instead review the goals of pkgar and some examples that demonstrate its

design principles.

pkgar has the following goals:

- Atomic - Updates are done atomically if possible

- Economical - Transfer of data must only occur when hashes change, allowing for network and data usage to be minimized

- Fast - Encryption and hashing algorithms are chosen for performance, and packages can potentially be extracted in parallel

- Minimal - Unlike other formats such as

tar, the metadata included in apkgarfile is only what is required to extract the package - Relocatable - Packages can be installed to any directory, by any user, provided the user can verify the package signature and has access to that directory.